INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF PAPER HISTORIANS

Report on the IPH expedition to China

10 April-2 May 1999

Report on the IPH expedition to China

10 April-2 May 1999

On the 10th of April a small group of 14 people from 7 countries (USA, Holland, Germany, France, Denmark, Switzerland and Canada), half of whom are members of IPH, gathered in Shanghai for a two-weeks tour to central and northern China. Ten of the participants stayed for a third week, travelling to Yunnan Province in the South-West of China. The objective of this 'expedition' - staying in four star hotels for the most part, the trip didn't really deserve this denomination evocating images of adventure and hardship - was to visit sites where paper is still made by hand in the traditional way, to meet Chinese friends and colleagues involved in historical paper research, and to visit museums and historical sites.

Mrs. Elaine Koretsky, director of the Museum of Paper History and the Research Institute of Paper History and Technology, both in Brookline, Massachusetts (USA), had enthousiastically offered to organize this trip for members of IPH. The offer was readilly accepted because Elaine Koretsky has done such 'papermaking pilgrimages' several times before, not only to China, but also to other South-Asian countries like Thailand and Burma. With this experience and so many contacts in China already, and being one of IPH's most knowledgeable members of hand papermaking in Asia, she was the ideal leader of this expedition. Her husband Dr. Sidney Koretsky added an extra dimension to the trip, not only for his broad knowledge of papermaking - and visually documenting the processes - but also for his great storytelling and sense of humor (see ill.).

The group also had some excellent local guides at its disposal, as well as a most proficiant and charming national guide - rather the national guide as far as the participants were concerned - mrs. Hu Nai Qin (christianed "Jennifer" Hu), director of the Beijing Tourism College Travel Service (e-mail TCTS@263.net). Having already guided World-VIP's like former US President Jimmy Carter, the IPH tour seemed peanuts to the experienced and fluently English speaking Jennifer (see ill.), but IPH President Albert Elen turned out to be equally demanding, so this was again a real challenge for her. And she really did a magnificent job.

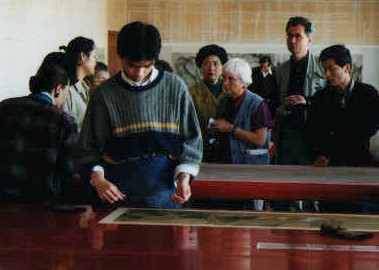

Apart from the tourist sites in Shanghai, on April 13th the group visited the newly built Shanghai Museum,

which houses the largest collection of Chinese cultural relics. We were greeted by Chen

Yuansheng (see ill.), research fellow and head of the biochemical group of the museum's Research Laboratory

for Conservation & Archaeology, who gave us an exclusive tour through the paper conservation

department (see ill.).

Apart from the tourist sites in Shanghai, on April 13th the group visited the newly built Shanghai Museum,

which houses the largest collection of Chinese cultural relics. We were greeted by Chen

Yuansheng (see ill.), research fellow and head of the biochemical group of the museum's Research Laboratory

for Conservation & Archaeology, who gave us an exclusive tour through the paper conservation

department (see ill.).

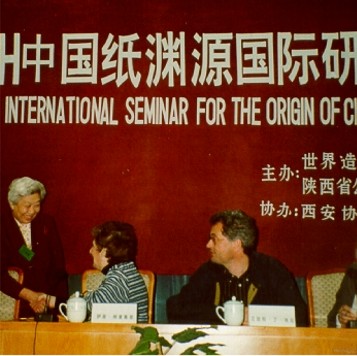

The Xi'an seminar was officially opened on April 15th in the Science Centre of the Shaanxi

Teachers University with a lot of media attention. China is justly proud of being the cradle of

papermaking and a number of cities or regions claim a

prominent place in its early history. Representatives of several cities and organizations

involved in Chinese paper history were present (see group photograph), including the Fujian Technical Association of

Paper Industry (Chen Qi Xin, vice-chairman and secretary-general), Shaanxi

University (Yang Juzhong, assoc. professor), Yanxian Cailun Academic Research Association

(Lei Yude and Duan Juigang), and Shaanxi History Museum (Yang Dongchen, professor) and last-but-not-least the Pulp and Paper

Industrial Research Institute of China (IPH-member mrs. Wang Ju Hua, senior engineer)(see ill. with mrs. Wang, Elaine Koretsky and Albert Elen).

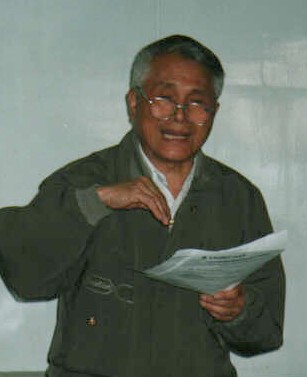

One of the most prominent speakers was professor Chen Xuehua (see ill.), who was involved in the finding of early paper fragments, made from hemp fibres mixed with a small amount of ramie, during excavations in the Baqiao township, a suburb of Xi'an, back in 1957. He strongly believes paper was made and used for several daily purposes in the Western Han Dynasty (202-24 BC), long before the legendary Cai Lun stimulated the Chinese emperor to require the use of paper for the dissemination of all imperial edicts in the year 105 AD. The latter's main contribution was that he advocated the use of paper as a writing material, but he was not himself involved in papermaking.

One of the supporters of the Cai Lun doctrine, Chen Qi-Xin (see ill.), the author of several articles

on this issue, argued that, judging from the wording of the characters inscribed on them,

early fragments of paper found in 1982 were not from the Western Han Dynasty but the Eastern

Han Dynasty, that is Cai Lun's time.

One of the supporters of the Cai Lun doctrine, Chen Qi-Xin (see ill.), the author of several articles

on this issue, argued that, judging from the wording of the characters inscribed on them,

early fragments of paper found in 1982 were not from the Western Han Dynasty but the Eastern

Han Dynasty, that is Cai Lun's time. In the Shaanxi History Museum in Xi'an we had the opportunity to study the above-mentioned remnants of early paper excavated from bricks and tile works in a Han tomb in the Baqiao township and proudly presented by the museum as the earliest plant fibre paper in the world. From or through Xi'an the craft of papermaking spread by way of the Silk Route to Samarkand, Bagdad, North Africa, and ultimately to Europe, more than a millennium after its invention in China.

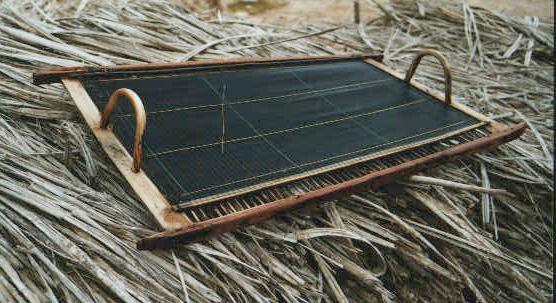

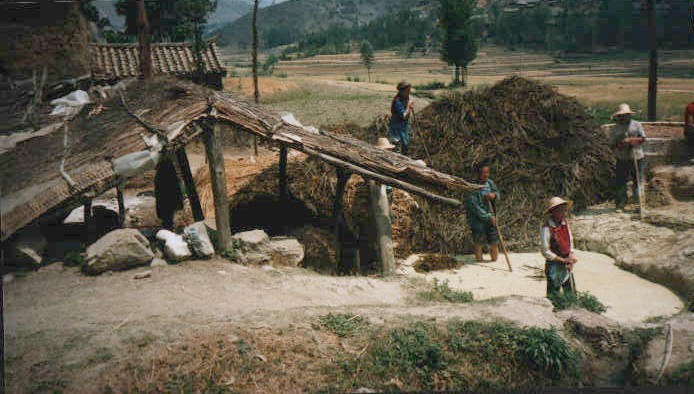

In between the opening of the seminar and the discussions, the group visited Li Fang's

hometown Bei Zhang village near Xi'an, where his family still makes paper by hand in the

traditional way, using mulberry fibres and a dipping mould and screen to form the sheets

(the oldest method of sheet formation is pouring dispersed fibres on a mould). The Bei Zhang paper

is made in a darkbrown spring variety and two white winter varieties. The sheets measure

approximately 41 x 43 cm. and 35 x 40 cm. respectively. A ninety-year old relative of Li Fang

demonstrated how paper was made standing in a pit outside the courtyard from a vat which is actually

dug out in the ground (see ill.).

In between the opening of the seminar and the discussions, the group visited Li Fang's

hometown Bei Zhang village near Xi'an, where his family still makes paper by hand in the

traditional way, using mulberry fibres and a dipping mould and screen to form the sheets

(the oldest method of sheet formation is pouring dispersed fibres on a mould). The Bei Zhang paper

is made in a darkbrown spring variety and two white winter varieties. The sheets measure

approximately 41 x 43 cm. and 35 x 40 cm. respectively. A ninety-year old relative of Li Fang

demonstrated how paper was made standing in a pit outside the courtyard from a vat which is actually

dug out in the ground (see ill.).

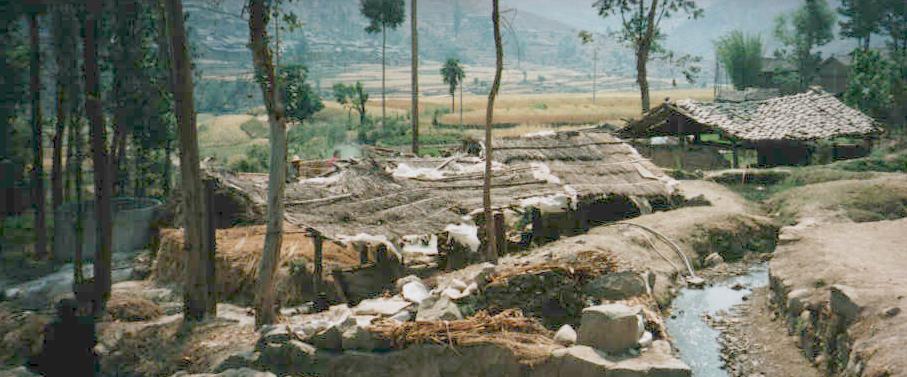

On April 16th we had our first real expedion day: a six-hours drive into the mountains south

of Xi'an, where we visited two villages in the Li Bien Xiao Ling township where paper is still

made by hand. The raw material used by the papermakers family in Chen Jia Wan

village in Zha Shui County is the inner bark of the mulberry tree. We witnessed a special beating

method with two men jumping up and down with a wooden stamper. This paper is used primarily

in the wine and liquor business to wrap the jars. It is also used to line the six interior sides

of coffins and to wrap the dead for burial. In this village more than 30 families are involved

in papermaking. In the other village bamboo is the primary material for papermaking.

The yang tao plant root is used as a formation aid.

In Lanzhou, the next stop on the Silk Route, the group visited the Institute of Archaeology for

Cultural Relics and the Museum of Gansu Province. In the institute we were welcomed by director

Yang Xiong and curator professor He Shuangquan (see the ill. of our hosts together with Elaine Koretsky and Albert Elen). They showed us the archaeological findings from

the excavations in Dun Huang in North-West China (below the Gobi desert) in 1990-92, which will

be published soon. The 400 remnants of early paper, the oldest known made of linen fibres, were

excavated from a building near a beacon tower. They are dated around 110-90 BC, on the basis of

other cultural relics found in the same layer dating from the reign of the emperor Wen Di (Western Han

Dynasty). The experts in Lanzhou do not believe the paper was actually made in that area, but

came there by way of the Silk Route. The paper fragments are well preserved because of the desert

climate and the fact that they were covered by solid soil instead of sand. The basic size of the

paper was probably around 33 x 22 cm and some fragments still show the impression of the screen.

In Lanzhou, the next stop on the Silk Route, the group visited the Institute of Archaeology for

Cultural Relics and the Museum of Gansu Province. In the institute we were welcomed by director

Yang Xiong and curator professor He Shuangquan (see the ill. of our hosts together with Elaine Koretsky and Albert Elen). They showed us the archaeological findings from

the excavations in Dun Huang in North-West China (below the Gobi desert) in 1990-92, which will

be published soon. The 400 remnants of early paper, the oldest known made of linen fibres, were

excavated from a building near a beacon tower. They are dated around 110-90 BC, on the basis of

other cultural relics found in the same layer dating from the reign of the emperor Wen Di (Western Han

Dynasty). The experts in Lanzhou do not believe the paper was actually made in that area, but

came there by way of the Silk Route. The paper fragments are well preserved because of the desert

climate and the fact that they were covered by solid soil instead of sand. The basic size of the

paper was probably around 33 x 22 cm and some fragments still show the impression of the screen.

In China's capital Beijing the group was invited by Huang Runbin (see ill.), the executive vice-president of the China Technical Association of the Paper Industry (CTAPI) and met some of the members of CTAPI's Paper History working group, who all belong to the Cai Lun school of thought. The Association has recently supported the erection of a monument and the writing of an opera devoted to the legendary Cai Lun.

During the meeting at CTAPI Mrs. Wang Ju Hua (see ill.), a member of IPH and also present at the seminar in Xi'an the week before, argued against the conclusions of the Lanzhou archaeologists that the paper remnants found in Dun Huang date from the Western Han Dynasty. According to her it is impossible to distinguish between Western and Eastern Han on the basis of earth layers. In her opinion the fragments are of much later date.

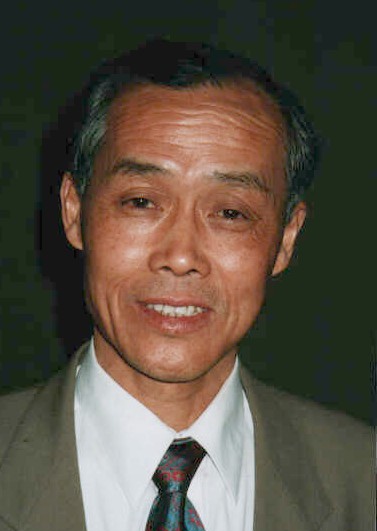

On another occasion in Beijing we also met Pan Jixing, professor of the history of science at the Academia Sinica. Professor Pan Jixing (see ill.) was our guest of honor at the farewell diner in one of the Peking Duck Restaurants as he is a long-time member of IPH and the author of an important book on the history of papermaking, which will be published in a revised English translation later this year. He belongs to the group of Chinese scholars who are convinced that paper was made much earlier than Cai Lun. In his opinion Cai Lun may have improved rather than invented the papermaking technique and played an important role in its spreading.

"First of all it is imperative that a clear definition of paper is agreed upon: paper is made of

vegetable fibers (cellulose, excluding silk which is protein), which are beaten or macerated,

mixed with water, bound by hydrogen iron bonding, placed on or dipped from a vat with a screen

(mould), which allows the water to drip out, forming a sheet to be dried and used. This definition

intentionally leaves out the purpose for which paper was made. Paper was probably first made for

all kinds of daily purposes and only later on for its main purpose for the centuries to come:

writing, drawing, painting and, eventually, printing".

"First of all it is imperative that a clear definition of paper is agreed upon: paper is made of

vegetable fibers (cellulose, excluding silk which is protein), which are beaten or macerated,

mixed with water, bound by hydrogen iron bonding, placed on or dipped from a vat with a screen

(mould), which allows the water to drip out, forming a sheet to be dried and used. This definition

intentionally leaves out the purpose for which paper was made. Paper was probably first made for

all kinds of daily purposes and only later on for its main purpose for the centuries to come:

writing, drawing, painting and, eventually, printing".

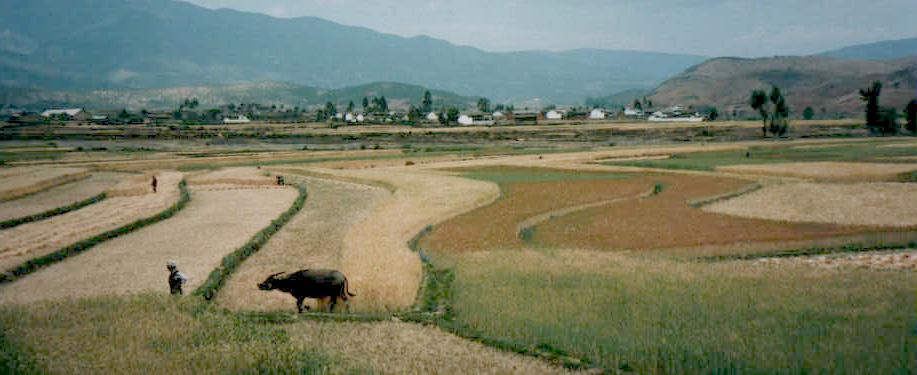

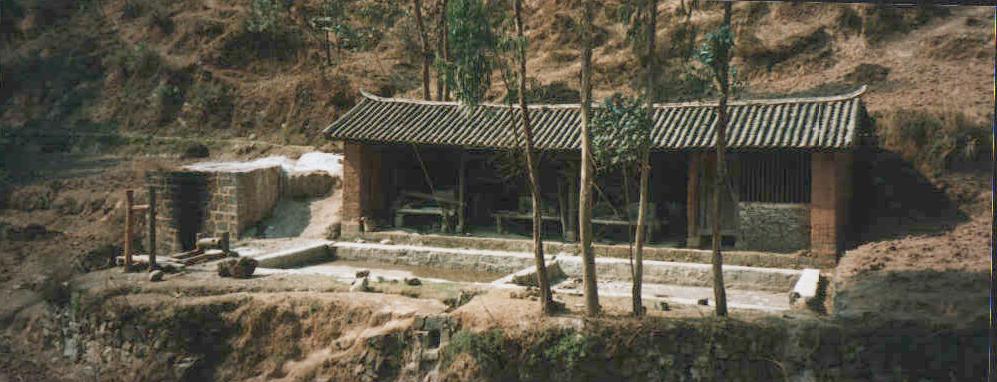

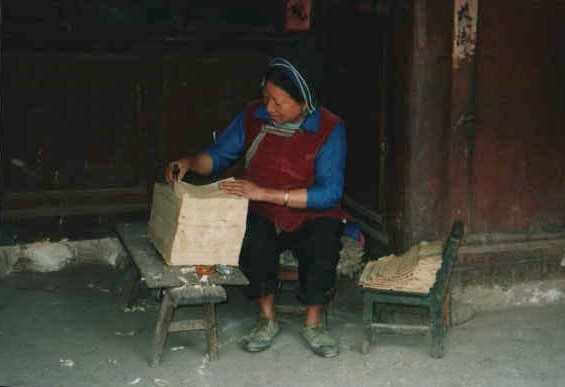

In Dadian village in Liuhi County near Hiu-In paper is made by the sixth or seventh

generation of papermakers. The mulberry paper is made with a dipping mould and a flexible bamboo

screen on it. As a formation aid the roots of the pine tree (pinus chinensis) are used.

Because the paper is used for painting and calligraphy a kind of resin is added to the pulp.

Unfortunately, we were not able to see the actual process of papermaking because

for lack of clean water in the village the papermakers were away to a creek somewhere down

the valley to wash and clean the mulberry bast used as the basic material. It would have taken

us too long to get there, so we stayed at the papermakers courtyard in the little village where

we were joined by most of the inhabitants who were as curious about us foreigners as we were about

their craft. The village chief demonstrated the beating of the pulp and the special way of drying

the paper sheets on the outside of an oven specially made for this purpose. In the other village,

which we visited the next day, we were luckier.

In Dadian village in Liuhi County near Hiu-In paper is made by the sixth or seventh

generation of papermakers. The mulberry paper is made with a dipping mould and a flexible bamboo

screen on it. As a formation aid the roots of the pine tree (pinus chinensis) are used.

Because the paper is used for painting and calligraphy a kind of resin is added to the pulp.

Unfortunately, we were not able to see the actual process of papermaking because

for lack of clean water in the village the papermakers were away to a creek somewhere down

the valley to wash and clean the mulberry bast used as the basic material. It would have taken

us too long to get there, so we stayed at the papermakers courtyard in the little village where

we were joined by most of the inhabitants who were as curious about us foreigners as we were about

their craft. The village chief demonstrated the beating of the pulp and the special way of drying

the paper sheets on the outside of an oven specially made for this purpose. In the other village,

which we visited the next day, we were luckier.

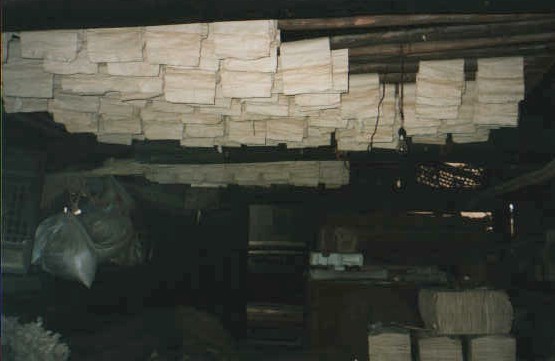

The way of drying the paper in the attic of the house on cords

is the same traditionally used in Europe since the earliest times.

Even a T-shaped stick is used to hang the wet sheets on the cords,

like in Western paper mills (see ill.). The reams also look

very similar (see illustration); the ream wrappers, however, were

reused pieces of cardboard.

The way of drying the paper in the attic of the house on cords

is the same traditionally used in Europe since the earliest times.

Even a T-shaped stick is used to hang the wet sheets on the cords,

like in Western paper mills (see ill.). The reams also look

very similar (see illustration); the ream wrappers, however, were

reused pieces of cardboard.

This is an electronic web version of an article Copyright 1999 by Albert Elen. Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted with or without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on services, or to redistribute to lists, requires specific permission and/or a fee.